Chapter 8 Book Excerpt: Leadership is Lonely

Audio Read by Dr. Jeff McCausland

Excerpt written by Jeff McCausland and Tom Vossler

As the fighting ended in the early evening of the second day at Gettysburg, Union commander George Meade and Confederate commander Robert E. Lee had decisions to make about what happens next. Confederate attacks that day had gained some ground to include more advantageous positions for their artillery. Still the Union defensive line remained largely intact in spite of heavy casualties in some defending units and retained control of the dominant terrain. Consequently, the second day’s fighting had proven indecisive. Meade and Lee now had to decide what a third day of fighting could achieve given what was left of their respective army’s combat power versus estimates of their opponent’s capabilities.

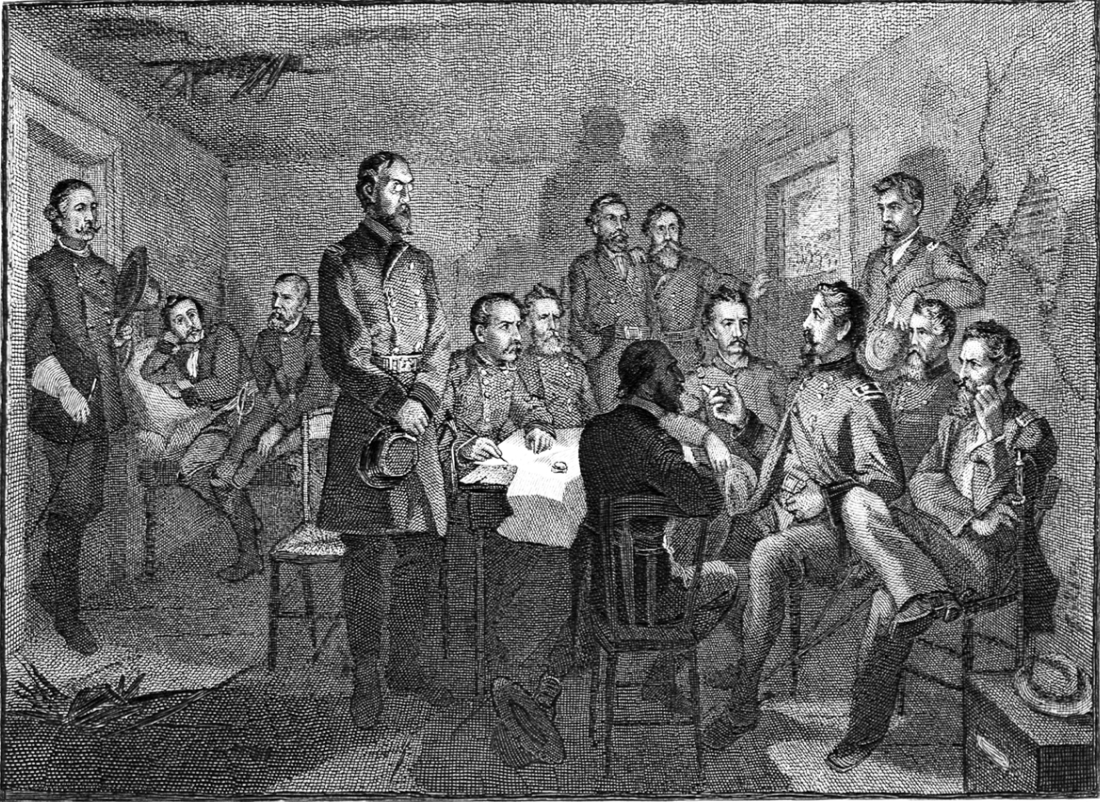

Meade, seeking to make informed decisions, called his senior subordinate commanders to his headquarters – the widow Leister’s house, located just east of Cemetery Ridge and south of Cemetery Hill. The Council of War began with each leader reporting the condition of his command following two days of battle. Their estimate of the situation included everything from ammunition available to morale of the troops. In the end, a course of action for a third day of battle was decided upon. The Army of the Potomac would continue to defend along the defensive line it currently occupied.

During the fighting on the second day Lee had observed the ebb and flow of the battle from an observation point on Seminary Ridge. Contemporary reports record that “Lee sat alone on a tree stump intently observing the movement of his infantry and artillery through field glasses, anxiously moving from one stump to another to get a better angle of view... while the battle raged, he sent only one message and received only one report by courier.”[i]

Lee’s decision cycle that evening was almost diametrically opposed to that conducted by Meade. Where Meade reached out for information and advice from his subordinate commanders, Lee kept his own counsel. Upon returning to his headquarters on the north end of Seminary Ridge just west of the town, he conversed with only two people. The first was the lamented cavalry commander J.E.B. Stuart whose troopers were just then rejoining the main body of the Confederate Army after a week-long absence. The second person with whom Lee conversed was Third Corps commander A.P. Hill. Their conversation was informal and brief. No record remains of it. One can only speculate as to their discussion.

Lee’s informal meeting with Hill was the closest he came to holding a Council of War. Contrary to his usual practice, First Corps commander James Longstreet (Lee’s ‘old warhorse’) did not seek out Lee after a day of fighting to discuss eventualities. Nor did Lee send for him. Similarly, Second Corps commander Richard Ewell did not trouble himself to go to Lee and report the condition of his command or seek orders for the next day. Like Longstreet, Ewell sent a staff officer to Lee’s headquarters as his representative to deliver a summary report.

General Meade’s July 2nd Council of War

Photo: USAMHI

LEADERSHIP IS LONELY, BUT REFLECTION IS IMPORTANT

Lee kept his own counsel that evening and did not call his immediate subordinate leaders together, seek their advice, or inquire about the state of their troops. Why did he do that? It appears he was extremely disappointed in his team, and it is likely that based on what had transpired during the previous two days his subordinates were reluctant to voice their views unsolicited. Lee appears to have believed that Hill and Ewell had let him down on the first day of fighting. Hill had gotten the army fully engaged in battle before it had been able to consolidate—disobeying Lee’s specific orders. Longstreet had not moved his corps as quickly as Lee had wanted on July 2, and this may have resulted in the Confederate army’s missed opportunity to achieve victory that day. Stuart had been missing for a week.

On the evening of July 2 Lee may have finally realized that his leadership style was no longer working. As previously mentioned, he had used a style that emphasized providing broad guidance and allowing his subordinates maximum flexibility. While this had worked in the past, it had failed over the previous two critical days. Before the third day, he took time for self-assessment and reflection, which is crucially important. While this may seem counterintuitive since leadership is all about relationships, leadership can also be a solitary, lonely experience.

Many experts argue that effective modern leaders must be “thinkers.” Those who can take time in solitude to consider what should be done and—perhaps more importantly—why.[ii] Thinkers who question the routine can formulate new ideas and directions with independence, creativity, and flexibility. Successful leaders today must have the courage to argue for ideas that may not be popular even when they fail to immediately please their superiors.

This can only be achieved if the leader not only takes his or her own counsel but, in the end, comes to a final decision. Many people might think solitude and leadership are contradictions, but solitude in reality is the essence of leadership. No matter how many people the leader consults, he or she is the one who ultimately must have the courage to make a hard decision. Lee had used a style that emphasized guidance, and now he may have believed that he needed to be more assertive. After all, at that moment, all Lee had was himself.

This requires concentration and the ability to focus on one issue long enough to develop an idea about it. Lee had perhaps an enormous advantage over modern leaders in this regard. He was leading his organization prior to the onset of the Information Age. In the nineteenth century it was relatively easy for a leader to find solitude anytime they wanted to concentrate on a problem, as Lee did on the evening of July 2, 1863. Today leaders are saturated continuously with information, questions, and entertainment from a variety of electronic sources. They are always connected, even though society did not make a conscious decision to surrender the bulk of its time for reflection in favor of time spent texting, tweeting, and staring at a screen.

It is difficult today—certainly harder than in 1863—but modern leaders need to mark off sixty to ninety minutes daily for “time to think.” A leader can make it known that he or she does not text and only checks email periodically—or at a certain point during the workday—and will neither write nor respond to emails on weekends. This approach will not occur without cost. Emails will go unanswered for hours rather than minutes, subordinates might have to wait for meetings with the boss, and other meetings may be postponed. But scheduling a time to think and reflect is not a zero-sum game. Fundamentally, a leader must decide whether reflection and hard analytical work are important.

There is a second potential price for a change like this, however. The usual social adherence to traditional organizational processes may be sacrificed to a degree in the name of nonconformity. If a leader does this without explanation, it could lead to the impression that she or he is aloof, arrogant, unapproachable, and even uncaring. He or she must make it clear in as much detail as necessary that doing the organization’s essential work requires time to think. It may also have ancillary benefits, as it can serve to reinforce a leader’s desire to encourage initiative throughout the organization and encourage mid-level leaders to make decisions. But ultimately leadership can be lonely.

[i] Edwin B. Coddington, The Gettysburg Campaign – A Study in Command (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968 (p. 444)

[ii] William Deresiewicz, “Solitude and Leadership” (lecture delivered at the United States Military Academy at West Point, March 1, 2010). See also Raymond M. Kethledge and Michael S. Erwin, “It’s Lonely at the Top—or It Should Be,” Wall Street Journal, June 19, 2017.

Parts of this article are excerpted and adapted from Battle Tested! Gettysburg Leadership Lessons for 21st Century Leaders written by Jeffrey D. McCausland and Tom Vossler. The book is available now! Order your copy at: https://bit.ly/battletestedbook.